“We forget our troubles”: crystal meth use rises in Zimbabwe

Harare’s drug dealers say business is booming as more young people, some at school, use mutoriro

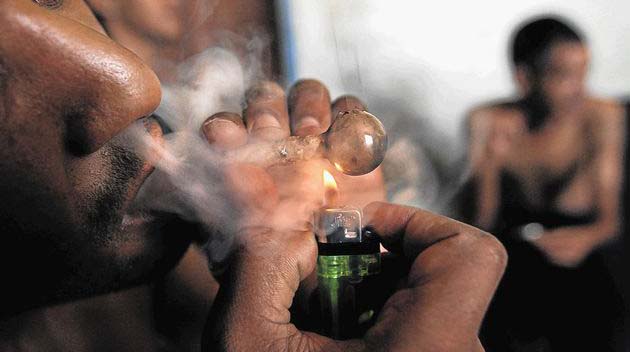

Inside a tiny room in Kuwadzana, a township in Harare, Solomon Sigauke* and his friends talk animatedly about football and listen to loud music. The misty vapour from the crystal meth fills the room as they take turns on a fluorescent pipe.

Sigauke, 25, has no cigarette lighter so he is improvises, holding a burning candle while his friend Kudzo puffs the smoke from the burning substance, known locally as mutoriro. .

‘You are beautiful’: the Kenyan beauty parlour serving female heroin users

It is 7pm in Kuwadzana, about nine miles from Harare’s central business district, where many youths have ventured into illicit and dangerous drugs such as mutoriro, with the numbers rising as the lockdown cut them off from jobs and their usual social lives.

Known scientifically as methamphetamine, crystal meth is a highly addictive stimulant used for its powerful euphoric effects.

Sigauke demonstrates the process of decrystallising the white chemical into a brown smoking smear. The curved pipe is made from fluorescent tubesfrom disused energy-saver lightbulbs that are cleaned and sold to drug users for $1.

As he exhales a cloud of the toxic smoke, his friends burst out laughing at Sigauke’s drooling face. “You should be careful not to ingest the smoke because it causes stomach-ache,” Sigauke explains.

We live in a world of our own

‘Solomon Sigauke’

Although the drug has been used in Zimbabwe for some years, its use has grown in the townships as the economic crisis grips the country, leaving few job prospects for its young people. Zimbabwe has nearly 90% unemployment, with young people worst affected.

“This drug will just make you get into another zone altogether; we can spend the whole night talking and enjoying ourselves. We live in a world of our own and can even forget about our daily troubles,” Sigauke says.

He adds that as schools have closed because of the Covid pandemic, teenagers are now joining their ranks.

“These days you find little girls taking the substance. Most of them are coming here to smoke this thing. At 1am, you will find most kids flooding the streets smoking meth – it’s like you are watching a movie. These children have become wild,” Sigauke says.

A gram of crystal meth costs $12 – a steep cost for most users in the townships and equivalent to a week’s rent on a room in a township. The drug-pushers have taken advantage of the use of foreign currency as legal tender in the country to milk the drug-thirsty market. One supplier explains that crystal meth is smuggled into the country through Zimbabwe’s porous borders with South Africa.

A child scavenges for plastic waste and cardboard for resale in the Harare township of Warren Park. Zimbabwe’s economic crisis means there is no treatment for most drug addicts. Photograph: Aaron Ufumeli/EPA

“If I had money, I would buy it every day,” Sigauke says.

Mbare, the oldest and one of the most populous suburbs in Harare, is notorious for drug abuse. “Blah” Bullet sells crystal meth there. He says the market is growing fast, explaining that before it had only been youths in the affluent suburbs who could afford it, but now young people are turning to the drug in townships, where there is little else on offer.

Bullet makes $200 a day from his sales, which have grown since the start of the lockdown in Zimbabwe last March, and has a network of drug spots around the city where he also sells other drugs such as cannabis, as well as prescription drugs that commonly misused such as codeine, the cough syrup Broncleer, which contains codeine, and pills that are usually prescribed to combat mental illness.

Despite the prohibitive costs, many addicts find a way to fund their insatiable appetite by selling their possessions, while others are driven to steal.

Sigauke was thrown out of his parents’ home last year after selling their electrical appliances. His addiction has led to frosty relations with his father, his friend Marlon Muchaka, 24, says.

“His father does not want to see him. He almost reported Solo to the police because of his behaviour,” Muchaka says .

“There are people who say this drug is dangerous, but people continue to use it because it is not that deadly. I left other drugs because they do not give me the satisfaction I need,” Sigauke says.

“Sometimes I find myself getting agitated and angry – I do not like the way I feel but it is the drug. I find myself saying things I regret. I am just a free-spirited person when I am intoxicated,” he says.

I can work all night without even dozing … But I don’t advise the young ones to get this drug

‘Donald Mabhuku’

“My sleeping patterns have been disturbed by this drug. Last year, due to excessive use, I failed to sleep for a week and by the time I finally slept, it took me two days to wake up. My landlord thought I had died inside my room. That is when I was advised to take it slow,” Sigauke says.

Donald Mabhuku*, 29, is a security guard living in the Harare township of Highfield. He says the drug helps him stay awake during his night shifts.

“I like this stuff, it just does it for me. I can do my work all night without even dozing. It is good if you want to do something productive with your time. But I do not advise young ones to get this drug,” he says.

An emaciated Mabhuku has experienced extreme weight loss since he started using the drug two years ago. “I lost a lot of weight due to excessive use of meth; it was bad but now that I am getting used to it, I am regaining my weight. But eating is still a problem. Most people lose weight because of lack of sleep,” he says.

A street in Kuwadzana. Crystal meth used to be only found in more affluent suburbs but has spread to the townships. Photograph: Cynthia Matonhodze/Guardian

Smoking crystal meth comes with its own culture and has its own slang, and is often associated with Zimdancehall music.

“We have our own language here. Our language is like reverse words, so that no one else understands what we are talking about,” Mabhuku says.

Natasha Chipendo* is also addicted to crystal meth and has ran away from home. The 22-year-old has tried to quit in the past. “I just find myself going back to it,” she says.

With many young people battling drug addiction, the health system has been found wanting. Zimbabwe’s hospitals cannot treat addicts and the few rehabilitation centres are expensive. Peace Maramba, an expert in mental health, says the lack of public rehabilitation centres has worsened drug-induced mental health issues in the country.

“In Zimbabwe we do not have rehabilitation centres in government institutions. It is unfortunate that mental health has been neglected for long but I am glad that through funds from the World Health Organization there is hope that we can help more people,” Maramba says.

He says accessing any mental health services is prohibitively expensive for young people from the townships, and blamed the use of illicit substances on peer pressure and Zimbabwe’s unrelenting economic problems.

While rehabilitation is achievable for drug addicts, Maramba says most drug users often relapse when they have nowhere to go but back to the shanty towns where the peer pressure they faced before remains along with the same daily problems.

- Names have been changed.

… we have a small favour to ask. Millions are turning to the Guardian for open, independent, quality news every day, and readers in 180 countries around the world now support us financially.

We believe everyone deserves access to information that’s grounded in science and truth, and analysis rooted in authority and integrity. That’s why we made a different choice: to keep our reporting open for all readers, regardless of where they live or what they can afford to pay. This means more people can be better informed, united, and inspired to take meaningful action.

In these perilous times, a truth-seeking global news organisation like the Guardian is essential. We have no shareholders or billionaire owner, meaning our journalism is free from commercial and political influence – this makes us different. When it’s never been more important, our independence allows us to fearlessly investigate, challenge and expose those in power. Support the Guardian from as little as $1 – it only takes a minute. If you can, please consider supporting us with a regular amount each month. Thank you.

The Guardian